Copyright © 2023 All rights reserved. Privacy Policy

Oscar Wilde

A gentle and exceptionally gifted man born a hundred years before his time.

I bought my first book on Oscar Wilde in the 1970s. I can't remember what prompted me to do so, except I've always preferred reading non-fiction and biographies in particular. I was immediately hooked and now have around fifty books in my collection about, and by, Oscar Wilde.

Every year sees the interest in his life and work grow: his stories, wit and insights into the human condition never losing their relevance, and the tragic arc of his rise and fall never losing its fascination.

But what exactly is this fascination? How can I inflict you with this sweet obsession?

Oscar Wilde is the undoubted king of quotable quotations. They occur throughout his writings but most especially in his plays of Victorian drawing room manners where he took delight in sending up the very social class that feted and admired him (until his fall that is).

Many of his aphorisms and witticisms were verbal and written down by others. There are also some attributed to Wilde but may not have actually been said by him at all, for example “I have nothing to declare except my genius”.

There is no doubt however that one of the numerous reasons for Oscar Wilde’s continued fame is the amazing relevance his quotations still have after over 120 years. I’ve used some as chapter headings in what follows.

Master of

the bon mot

- Born 1854, died 46 years later an exile in Paris

- Full name: Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde

- Ruined by a fatal attraction

- Lived out his own maxim: “The artistic life is a long, lovely suicide”

- The first ‘celebrity’

Born at 21 Westland Row, Dublin in 1854, Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde had a set of eccentric parents. His father, Sir William Wilde was a noted eye and ear surgeon, author and philanthropist, who had several illegitimate children from extramarital affairs, one of which resulted in an embarrassing court case - an early echo perhaps of his son's fate. Oscar's mother, controversial poet and novelist Lady Jane Elgee Wilde, was a flamboyant and unconventional woman (for her time), and an Irish nationalist who fought for women's rights. She went by the pen-name of "Speranza". She had wanted a daughter rather than a second son, and for many years the young Oscar was dressed only in girls' clothing. (Too much store shouldn't be set on this in terms of explaining Oscar's future predilections - it was not uncommon at the time). He had an elder brother, Willie, and a younger sister, Isola, but she died at the age of eight, which affected the twelve-year old Oscar deeply. He had been close to his little sister and he later wrote the beautiful poem Requiescat to perpetuate her memory.

Wilde's story is mesmerising because it can be appreciated on many different levels, and therefore by many different people. For me the main fascination is the heart-rending tragedy of his downfall and early death; and the challenge of studying in detail the events leading to these so as to better understand the actions and motives of all the colourful characters involved. And as with all really tragic stories I sometimes find myself reading about the closing years of his life wishing that this time the ending would change and tragedy averted.

For a man who championed Greek ideals his sparkling rise and pitiful fall were certainly of epic proportions and in some ways even heroic. His character was shot through with paradox. He lifted up the hearts of nearly everyone he met and broke some of those same hearts. He was a wonderful and doting father to his two children and an adoring husband, and yet he also treated his wife cruelly in conducting his affair with Bosie Douglas. Oscar was a brilliant conversationalist, wit, poet and playwright and left a wonderful permanent legacy to English literature. His exquisite comedies of manners such as The Importance of Being Earnest and An Ideal Husband deal with eternal verities in personal relationships and social constructs and therefore still charm audiences today. He cherished beauty and art above all else. He was the first modern 'celebrity', touring the USA in 1882 lecturing on matters of fashion and The House Beautiful to great acclaim and curiosity. He was the leader of the 'fin de siecle' aesthetic movement which influenced trends in poetry, painting, bookbinding, fashion and many other artistic spheres, and his death in 1900 marked the end of that movement. All these add up to one major fascination, and that is how Oscar Wilde was obviously ahead of his time in so many respects. His downfall could only have occurred in Victorian England and yet could even have been avoided. But as Oscar himself put it, "Like an ox I stumbled into the shambles."

When reading about Oscar Wilde all human life is there, as they say. His story is like a vivid Victorian soap opera with shocking twists and turns in plot lines, taking in on the way love, hate, sex, treachery, fame, success, conspiracy, blackmail, dramatic courtroom scenes, prison, redemption and finally death. The fascination is made all the more compelling by the fact that all these things really happened to real people, and the impacts of these events have reverberated down the years, not least with the descendants (see Footnote 1) of the chief protagonists, and will continue to do so.

Please take a few minutes to read what follows and try one of the recommended books at the end. I promise you will be drawn in to a wonderful world and begin your own lifelong love affair with the icon that is Oscar Wilde.

It is no use for me to address you, people who can do these things must be dead to all sense of shame... I shall be expected to pass the severest sentence that the law allows. In my judgement it is totally inadequate for such a case as this. The sentence of the court is that you be imprisoned and kept to hard labour for two years.

- Mr Justice Wills

On 26 May, 1895, with these words, the career, reputation and ultimately the life of one of the world's greatest playwrights was brought to an end.

The one duty we owe to history is to rewrite it

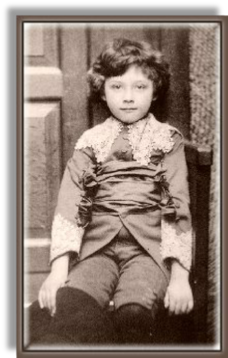

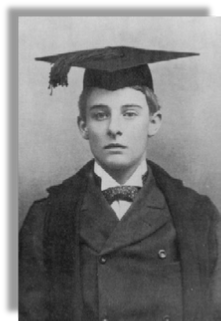

Oscar as a child

Oscar was educated at home until he was nine. and then sent with his brother Willie, to Portora Royal School for boys at Enniskillen (motto: 'Honour All Men'). Fascinated by a celebrated court case, he once said to some of his fellow pupils that nothing would please him more than to be the principal in such an action, '..to go down to posterity as the defendant in such a case as "Regina verses Wilde"'.

He shone at his studies and in 1871 was one of three pupils awarded a scholarship to Trinity College, Dublin. His name was duly inscribed in gilt letters on Portora's alumni board, but in 1895, the year of his disgrace, it was painted out, and the initials OW which he'd carved by the window to a classroom were scraped away. Now his name has been regilded. How disappointing then that the history page on their web site today only devotes one sentence to their most illustrious old boy - even spelling his name incorrectly ('O'Flaherty').

Oscar studied the classics at Trinity College, Dublin until 1874, when he was 20. He was an outstanding student, and won the Berkeley Gold Medal, the highest award available to classics students at Trinity. One of his friends there was Edward Carson, who in later years was to lead for the prosecution against him.

Children begin by loving their parents; after a time they judge them; rarely, if ever, do they forgive them.

Oscar aged eight

No.1 Merrion Square, Dublin today, where the Wilde family lived until it was sold in 1879, and the 'Speranza' dining room

He was granted a scholarship to Magdalen College, Oxford, where he continued his studies from 1874 to 1878.

He dispensed with his Irish accent at Oxford to better fit in; adopting a stately and distinct English tone. He also underwent a sartorial revolution, developing a great appetite for formal wear and which shortly evolved into dandyism. He joined the Freemasons (his father had been one), largely because it was fashionable at the time but also because he admired the elaborate regalia.

However, he was tall and strong, 'far from being a flabby aesthete' according to one contemporary, and took part in rowing and boxing. He was dismissed from the rowing crew because of his languid strokes, "I don't see the use of going down backwards to Iffley every evening." One evening some junior common room types decided to visit Wilde's rooms and break up his furniture. Four were deputed to burst in whilst the rest watched from the stairs. The result was unexpected. Oscar booted out the first, doubled up the second with a punch, threw the third out through the air, and carried the fourth - a man as big as himself - down to his rooms where he buried him in his own furniture.

The biggest influences on Wilde's development as an artist at this time were Swinburne, Walter Pater and John Ruskin. His reckless side began to manifest itself as well. It's while at Oxford that he is rumored to have contracted syphilis after a night with a female prostitute. Part of the basis for this rumour is that his teeth were blackened and he usually covered his mouth with his hand while talking. In the 1870's medical authorities prescribed a (useless) course of mercury for syphilis and this turned the patient's teeth black. This rumour is still hotly disputed, but propounded by one of his major biographers, Richard Ellman (see Footnote 2) based on other comments made by close friends of Wilde's. Also, it seems Wilde was troubled spiritually at this time and came close to becoming a Catholic as he ever would until his deathbed.

Nevertheless, Oscar of course shone academically while at Magdalen, culminating in his winning the 1878 prestigious Oxford Newdigate Prize for his poem Ravenna. He graduated with a rare double first at the age of 24.

The whole theory of modern education is radically unsound. Fortunately, in England at any rate, education produces no effect whatsoever.

After graduating from Magdalen, Wilde returned to Dublin, where he learned that a girl he'd fallen in love with three summers before, Florence Balcombe had became engaged to Bram Stoker, an enterprising Irish civil servant and drama critic with better immediate prospects and who was later to write 'Dracula'. Wilde wrote to her a proud and eternal farewell, stating his intention to leave Ireland permanently. He left in 1878 and was to return to his native country only twice, for brief visits. Oscar wrote about Florence to Ellen Terry, the famous actress, saying, 'She thinks I never loved her, thinks I forget. My God how could I?' But in London later on they would become friends again.

Once his studies had been completed, Wilde moved to London, but for two years or so found it difficult to find his way into the right circles, despite submitting articles and 'networking' as hard as he could. With funds dwindling - he'd nearly exhausted the modest inheritance his father had left him in 1876 - he even applied in 1880, unsuccessfully, to be a schools inspector, confiding in a letter to a friend at the time that he had not '..set the world quite on fire as yet'. He was however slowly establishing a reputation for himself as a great wit and eccentric. He was intent on becoming famous and a leading member of society and associated himself with many of the famous actresses of the time, including Lillie Langtry (mistress of Edward VII) and Sarah Bernhardt, and by so doing was becoming noticed. In 1879 his mother and his brother Willie also moved to London, his mother unable to keep up the Dublin home which, like almost all their other properties, had been found to be heavily mortgaged when Oscar's father died. (There was speculation that large amounts of money had been going to Sir William's paramours).

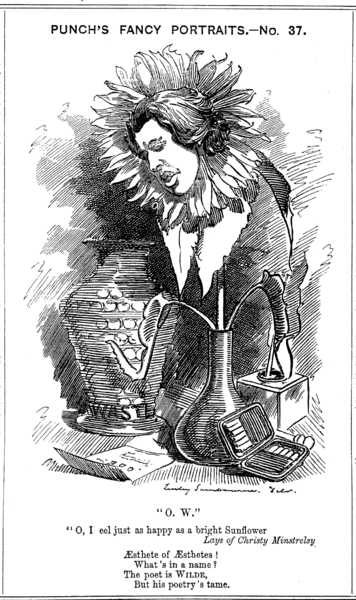

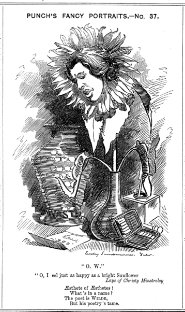

Oscar's impact on London society as the leader of the aesthetic movement was so great that he soon became the subject of satirical pieces in Punch (see cartoon below) and other magazines, in his role of the chief protaganist of the aesthetic movement. Before long even Gilbert and Sullivan had included him - under the name 'Bunthorpe' - as a character in one of their operettas, Patience. Wilde's witticisms became legendary as stories about him spread through social circles. He was seen as flamboyant, often dressing in knee breeches and lace cuffs. At a reception he reportedly greeted someone with the biting line: 'Oh I'm so glad you've come! There are a hundred things I want not to say to you.' At a lunch party he declared that there was no subject upon which he could not speak at a moment's notice. One man raised his glass and said 'The Queen', to which Oscar replied 'She is not a subject.'

Cashing in on this newfound notoriety, Wilde published his first play Vera. But this was poorly received and was to be rejected by a succession of theatre managers. A year later, in 1881, Oscar published a collection of his poems. Again, the critical reception was poor. One of the most galling responses was that of the Oxford Union which, after their librarian asked Oscar for a copy, voted to reject the inscribed copy 188 votes to 180. Many thought the man's verse owed far too much to other, well-established poets, notably Keats, but Wilde thought (probably correctly) that the rejection was more to do with his ideas being shocking to the provincial, conventional, pious English temperament. But he had no intention of changing. Wilde earned little money from the volume. Nevertheless he was becoming ever more popular not only amongst the artists community but also the aristocratic dinner party set, where his sparkling wit and bon mots made him an essential guest very much in demand, even if many of those present didn't always subscribe to his cynical and mischievous take on their mores. Oscar was also observing and absorbing; many of these people becoming caricatures in his later successful plays of drawing room manners.

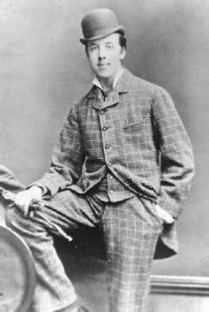

Oscar at Oxford 1876

Satirised in ‘Punch’ 1881

Wilde badly needed a new source of income. For this reason, in October 1881, at the age of 27, he accepted an offer to lecture in the United States. The operetta Patience had been very successful in the UK, and the American public were anxious to know more about the man who had inspired one of its principal characters. It was a publicity masterstroke on the part of Richard D'Oyly Carte - Patience had opened in September in New York and would be boosted by the presence on lecture tour of its main protagonist - 'Bunthorne'. Equally, Patience would generate interest in the lecture tour. Declaring his genius to the customs men in New York on 2nd January 1882 when he arrived on the SS Arizona, Wilde began a highly successful tour.

There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.

I have nothing to declare but my genius

Wilde's legend grew with each lecture he delivered. Many Americans came simply to laugh at the man, one or two lectures almost becoming farces, and some newspaper reviews mocked the aesthete, although one review did make the point, 'Hyper-aestheticism might be useful as an antidote to America's hyper-materialism'. The public were at least willing to pay him for his time and Wilde enjoyed himself; being feted wherever he went, accompanied by his own business manager and negro valet supplied by D'Oyly Carte, and pestered in every town and city by newspaper reporters demanding interviews.

It is a vulgar error to suppose that America was ever discovered. It was merely detected.

He also enjoyed highlights such as meeting the poets Walt Whitman and Henry Longfellow. Oscar was enjoying rock star status one hundred years before it was invented! His tour criss-crossed the USA, into Canada and then back to the USA, with about 150 appearances between January and October 1882 with lectures on such topics as 'Principles of Aestheticism', 'The English Renaissance', 'The House Beautiful' and 'The Decorative Arts'. Like all astute touring artists, he incorporated into his talks comments on local features which helped endear him to the new audience. On a stop in Leadville, Colorado, Wilde remarked that a saloon sign stating "Please do not shoot the pianist. He is doing his best." demonstrated 'the only rational method of art criticism I have ever come across'.

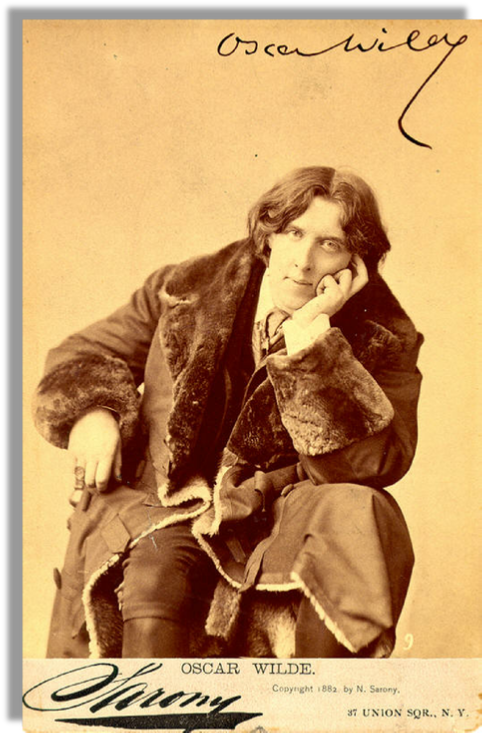

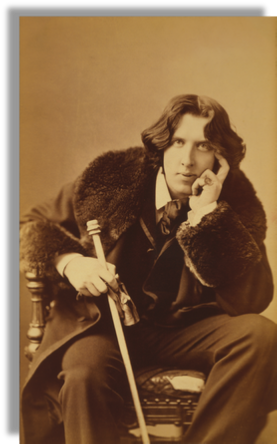

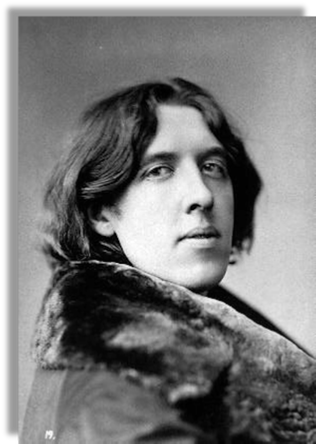

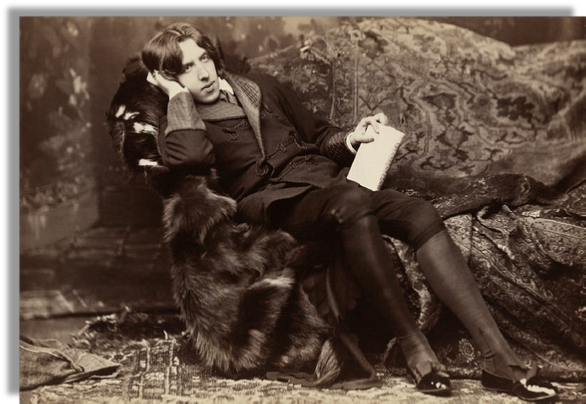

As befitting a celebrity, Wilde was photographed by the top New York society photographer, Sarony, and souvenir images were sold in large quantities like the ones below:

America has been discovered before but it has always been hushed up.

Autographed Sarony photo 1882

The lecture tour had been very lucrative (one recent estimate puts the net take after expenses at c.£74,000) and Wilde gathered sufficient funds to support himself very comfortably for a time on his return to Europe. But Oscar was now used to a certain opulence and in January 1883 went to stay in Paris. He had his hair cut in the style of Nero and changed his wardrobe again; giving up his 'American costume' and dressing almost like a French dandy of the period - cuffs turned back over jacket sleeves. tight trousers, coloured handkerchief and heavy rings. In between meeting other artists and generally passing the time, Wilde wrote some poetry and he finished his blank-verse drama The Duchess of Padua. He parodied his own indolence: 'I was working on the proof of one of my poems all the morning' 'And in the afternoon?' 'In the afternoon? Well, I put it back in again'. Oscar returned to London in May, strapped for cash again.

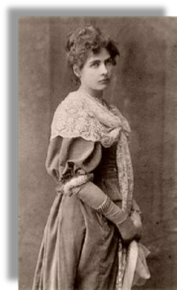

It's possible that at around this time Oscar's suppressed homosexual inclinations may have been stirring. Although he'd been with a notorious prostitute in Paris (who was later murdered) he'd also befriended Robert Sherard, a 21 year old would-be poet who was young, blond and idolatrous - the first in a long line of similar Wilde acolytes. Oscar's mother had been urging him and his brother Willie to settle down into 'good' (prosperous) marriages. A 'good' marriage would silence the gossip (Punch had recently called him a 'Mary-Ann'), save him from the moralists, and a rich one from the moneylenders. After a couple of refusals (sending a note to one, Charlotte Montefiore: 'Charlotte, I am so sorry about your decision. With your money and my brain we could have gone so far'), Oscar pursued Constance Lloyd, a 'violet-eyed' beauty he'd first met two years before. Constance (below) was four years younger than him, and the daughter of a successful Dublin barrister. She was very accomplished: was interested in music, painting, embroidery, women's rights and could read Dante in Italian (and did), and was also logical, mathematical, and shy yet fond of talking.

Every great man nowadays has his disciples, and it is always Judas who writes the biography.

After a short lecture tour of the UK to raise some money - at nothing like the fees he earned in the USA - Wilde set sail for New York for the opening, at last, of his first play Vera. The audiences initially liked it, but the critics hated it and the audiences tailed off, with the play closing after a week. Oscar returned to England and went back to lecturing in order to pay the bills, covering about 150 venues in the Autumn of 1883.

He now decided to propose to Constance Lloyd. He was accepted, although her family had misgivings about Wilde's debts and insisted the date be postponed until he had cleared some more from lecture fees. They married in May 1884 and whilst on his honeymoon in Paris that an extremely significant event occurred that would mark a turning point in his life. He read a newly published book, A Rebours ('Against Nature') by J K Huysmans that had shook the French literary scene. The book's hero was a dandy, scholar, debauchee, with appetites beyond all example. It was the epitome of the fin-de-siecle decadence creed. 'Wilde drank of it as a chaser after the love potions of matrimony' (Ellman). His mind was starting to wander along dark avenues that up until now he had barred himself from visiting.

'I knew I should create a great sensation,' gasped the Rocket, and he went out.

The couple set up home together at 16 (now 34) Tite Street, Chelsea, London and for a time Oscar seemed content, but his finances were not in good order as he continued to live the lifestyle neither his income, nor Constance's, could support, even though she had brought to the marriage a £5,000 (about £0.5m now) advance on her trust and £250 (£25k) a year allowance from it. The redecoration alone of their new home to new high standards of interior design took over seven months and cost an enormous amount. So Oscar continued to tour the UK giving lectures on art, fashion and style until the Spring of 1885, supplementing that income with some journalism.

The proper basis for marriage is mutual misunderstanding.

Two photos from the same session of Constance Wilde aged 34 in 1892

The house at 16 (now 34) Tite Street, Chelsea (with blue plaque) where Constance and Oscar lived from 1884 to Wilde’s fall from grace in 1895. Picture from 2012 when a one bedroom flat converted from Oscar’s library was put on sale for £1.15m

1882: Photos from the session with New York society photographer Napoleon Sarony.

About 27 poses were taken. More about this famous series can be found here.

Prints of these bearing OW’s signature sell for around £20,000 as of 2012 and the prices keep rising.

Constance gave birth to their first son, Cyril, in June 1885 followed by Vyvyan in November 1886. According to some accounts Wilde was increasingly repulsed by Constance's pregnant body and though he remained fond of Constance he seemed to lose enthusiasm for playing husband. He was though, by all accounts an attentive father and loved playing with the children and conjuring up fairy stories for them.

Cyril Wilde in 1891

Killed in WWI 1915

Vyvyan Wilde in 1891

Vyvyan Holland (Wilde) in 1940

Died 1967

Wilde's extravagant life-style continued unabated but he found work as a reviewer for the Pall Mall Gazette, which brought in some much needed income. His literary reviews were highly thought of and his reputation continued to grow. Then in November 1887 he took over the editorship of The Lady's World magazine for Cassell's and immediately changed the pretentious and repressive title to The Woman's World. At first he took the work seriously, turning up for work at 11am on his appointed days but gradually the old indolence set in and he came in later and left earlier until his visits were so fleeting he'd ask his assistant to ghost his pieces for him. He seemed to have 'settled down' to a humdrum married life. But the exterior routines belied the true goings-on.

To love oneself is the beginning of a lifelong romance.

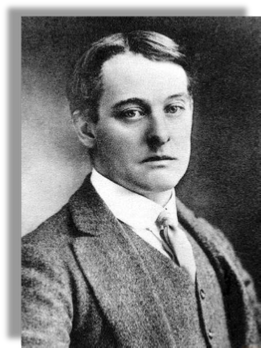

Around this time he gave in fully to his homosexual curiosity and was seduced by Robert Ross, a young Canadian student he met in 1886 who went up to Cambridge in 1888 but left early the following year when a bullying incident (he was thrown into a fountain) caused pneumonia and a mental breakdown. Wilde said Ross was 'wasting a youth that has always been, and will always be, full of promise.' Ross was 17 and Wilde 33 at the time of their first sexual incident. Ross would prove to be the most loyal friend Oscar Wilde ever had, ultimately becoming his literary executor.

I can resist everything except temptation.

Robert Ross in his 20s

Ross in 1911 aged 42

Homosexuality now fired Wilde's mind, or rather the 'Greek' ideal of it. Ironic frivolity, with dark insinuation, was the compound through which he now sought to express himself. To the rest of the world he appeared to have been lying fallow, but during the last few years he'd begun to think and talk the narratives and dialogues which he would write down - almost casually - over the next decade, crafting them into perfect literature. He was now constantly making the acquaintance of young men, who only had to be young, handsome and in awe of Oscar's wit and wisdom. Not all became sexual lovers: most often Wilde would enjoy the 'dance' more than the act, as well as the flattery of course and the group of young men who followed Wilde swelled with his success. He had no qualms about leaving behind him a trail of 'jilted' admirers whose only sin had been that they failed to amuse as much as the new arrival. Many of these young men became emotionally scarred for life by the sudden end of what must of been extremely intense periods in their lives. John Gray, the poet, having bathed in the bright light of Oscar's world as 'one of the more abject of Wilde's disciples' (Bernard Shaw) lost out to Bosie Douglas and finally became a Catholic priest as part of a vain lifelong quest to come to terms with his own contradictory feelings about the experience.

Not content with the company of possible or actual lovers, Wilde prided himself on leading not a double life but a multiple one, in his total commitment to life's sensations. He could be with cabinet ministers and royalty one night, with the most famous actors and actresses the next, and young men the next. And Constance, with his children, was always there, to neglect or not. Impossible as it may seem, Constance appears to have had no idea of her husband's homosexual dalliances throughout the ten years or so up until his downfall.

In 1885 a key event occurred in our slowly unfolding tragedy. The Criminal Law Amendment Act came into force which for the first time prohibited indecent relations between consenting adult males; and it saw in the age of the blackmailer. The penalty was prison for two years with or without hard labour. (When it was pointed out to Queen Victoria that women were not mentioned in the Act she is reported to have said, 'No woman would do that'). The Act was actually aimed at stopping the 'white slave trade' and came in response to the public when a journalist purchased a girl of thirteen for £5 to expose what was happening beneath the respectable facade of Victorian society. The Act was 'to make further provision for the Protection of Women and Girls, the suppression of brothels, and other purposes', but the indecency clause was an added amendment, remaining in force until 1967. (This didn't alter the law on sodomy which carried a maximum penalty of life imprisonment and was also in force until 1967).

1889 Photo Inscribed by Wilde to ‘Bobbie’ Ross

Constance and Oscar Wilde were now moving in larger circles. He'd stopped lecturing, and between 1886 and 1888 his main activity was a hundred or so literary reviews and the editorship of The Woman's World. Wilde increasingly sought analogues to his new mode of life so his own serious writing was starting to increase, dwelling frequently on themes such as masks, pretence, paradox, secrets, betrayal, transfiguration, redemption, and so on. He published a story The Portrait of Mr W.H about Shakespeare (a married man with two children...) and his supposed affair with Will Hughes, an actor. Oscar's reputation as an author really took off in 1888 with an entrancing book of fairy tales, The Happy Prince and Other Tales, and his output began to pick up speed. His inner circle understood the coded messages in much of his writing and so did others who were astute enough, but the subversiveness of his views was always overwhelmed by the grace and wit of their expression.

Like a lot of his writings, Oscar had been formulating the story in The Picture of Dorian Gray for some time in his dinner conversations and with his friends; the story of a man who remains young and beautiful while a portrait he keeps hidden away grows old in his stead as he indulges in terrible excesses. An American publisher, J M Stoddart, came to London in 1889 to promote his Lippincott's Monthly Magazine and entertained Wilde and Conan Doyle to dinner in order to persuade them to write stories for his magazine. They accepted. Conan Doyle offered his second Sherlock Holmes story The Sign of Four and Wilde would write up the story he told them, The Picture of Dorian Gray. After missing some deadlines the novel is published in Lippincott's in June 1890. Dorian is named after Wilde's lover at the time, John Gray, who takes the hint and later takes to signing his letters to Oscar, 'Dorian'. It's one of first books to bring homosexuality into an English novel, albeit thinly disguised, and Oscar pours into it much of the conversational glitter, fantasy and innuendo from the last few years of his life. He puts himself into the book in his various masks, explaining to someone later: 'Basil Hallward is what I think I am: Lord Henry is what the world thinks me: Dorian is what I would like to be in other ages, perhaps'.

There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well-written or badly written.

The Picture of Dorian Gray was an immediate success. It was then published in book form in April 1891 to similar acclaim. (Macmillan declined it because it had 'unpleasant elements' and a small firm Ward, Lock & Co. published it instead). There were sour notes: W H Smith refused to carry it and most critics charged Wilde with immorality (some even suggesting prosecution) choosing to ignore the obvious fact of Dorian's self-destruction. Wilde refuted the accusations in published replies, saying that all art was in any case amoral in nature - immorality did not come into it. The effect of the book was electric - nothing this exciting and controversial had been published in years. Wilde's circle of young men were ecstatic.

Meanwhile society's attitudes to 'unorthodox' practices were becoming more hostile. In 1889 the Cleveland Street Scandal had occurred. A male brothel had been uncovered where telegraph boys were found to be servicing not only 'gentlemen' but the nobility itself, including Prince Albert Victor the eldest son of the Prince of Wales, heir to the throne. The latter's involvement was strongly suspected (and confirmed by records released in 1975) but at the time the establishment managed to cover things up and the casualties were limited to a few Lords fleeing abroad. And so another part of the scene for Oscar Wilde's downfall was set.

An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all.

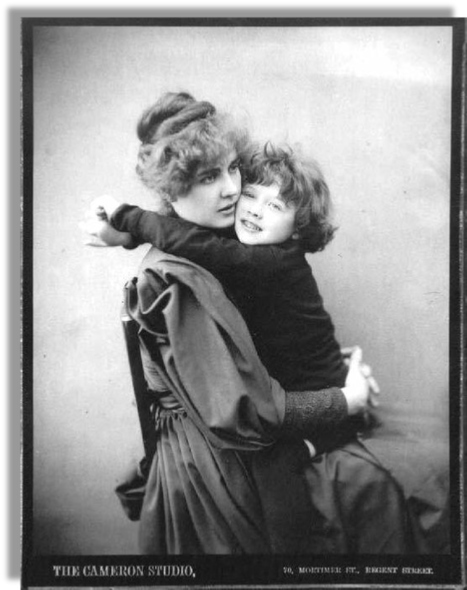

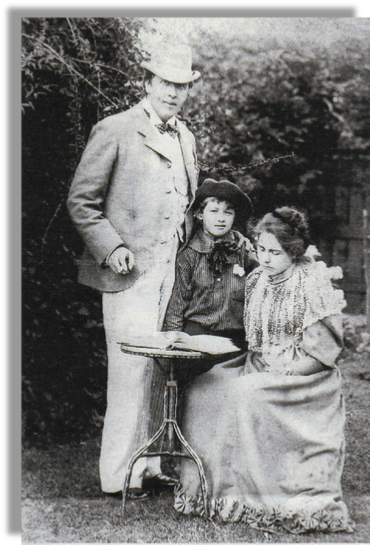

Constance and Cyril aged five November 1889.

A beautiful and unusual pose for the time.

Cyril was killed by a sniper's bullet in the 1914-18 War.

Merlin Holland, Wilde’s grandson, believes Cyril became a soldier "to prove himself as a man and ended up killed by a sniper in World War I, probably doing something foolhardy and heroic."

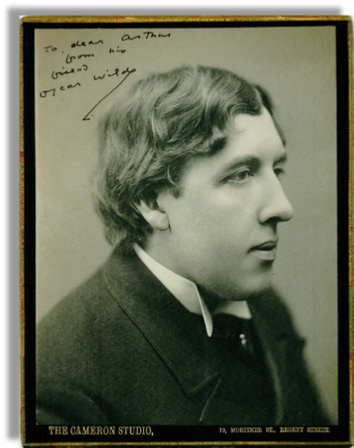

Same photo Inscribed by Wilde to ‘dear Arthur’.

This was Arthur Fish who had been Wilde’s very able sub-editor on the journal The Woman’s World from about 1887 to 1889 and spoke of him quite highly.

Fish, for his part, may have liked Wilde as a social acquaintance, but found his work habits a bit lacking: At first he took the work seriously and arrived at 11 a.m. on the appointed days, but gradually he came later and left earlier, so that his visit “was little more than a call.”

There was a quicker and easier way of making money than editing magazines, so Oscar gave up his post at The Woman's World to concentrate on his creative writing which would now pick up from a steady flow to an almost effortless torrent, driven by an alchemy of literary genius and secret appetites. Wilde began to play a game of charades whereby he impressed the literary world as well as entertaining a wider audience, amusing and teasing them at the same time. As Ellmann put it, 'Wilde is determined to find a justification for his sin'. In two acclaimed essays The Critic as Artist and The Soul of Man Under Socialism he explored contradictions in our concepts of art, beauty and sin. He proposed the importance of the artist (himself) moving the world towards self-recognition, even if this meant violation of some social norms. In Victorian society this was subversive stuff.

In June 1891 Wilde met for the first time the man that was to become his nemesis. One of Oscar's acolytes, Lionel Johnson, lent his copy of The Picture of Dorian Gray to his cousin who was at Magdalen College (Wilde's alma mater) and he became 'passionately absorbed' in it, reading it many times over. Johnson took his cousin to tea at Tite Street to meet Oscar, who gave a deluxe copy of his book to Lord Alfred Douglas, the youngest of three sons of the Ninth Marquess of Queensberry. Lord Alfred's family nickname was 'Bosie', a corruption of 'Boysie' which referred to his boyish extreme good looks. He was twenty years old, pale-faced, with blonde hair and blue eyes, and must have appeared an Adonis to Oscar. Although capable of aristocratic charm Bosie was utterly childlike, spoiled, reckless, and when crossed he could be explosively angry and cruel. He had come from a 'mad, bad line' and had his father's traits, but these went back much further. James, third Marquess of Queensberry, whose nickname was "the cannibalistic idiot", escaped in 1707 from his cell into the kitchens of Holyrood Palace, where he seized a cookboy, killed him and roasted him on a spit before the fire. (Bosie's own son, Raymond, spent most of his life in mental institutions, dying confined in one in 1964).

A cynic... a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.

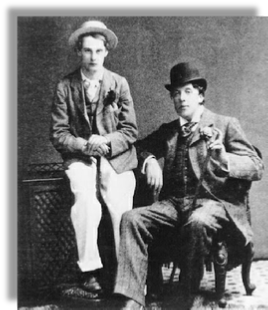

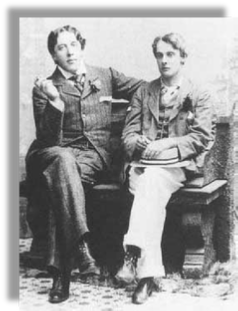

Lord Alfred 'Bosie' Douglas aged 21 at Oxford University in 1891.

1891 was a very busy year for Oscar. He spent some time in Paris visiting like-minded artists, all the while formulating his play Salome. In December he came back to spend Christmas with his wife and sons and then went to Torquay to finish Salome and put the finishing touches to Lady Windemere's Fan, A Play About a Good Woman which was due to open in February. Oscar's first theatrical success, it was staged at St James to exceptional acclaim. His wife attended the opening night, as did Oscar's acolytes and one Edward Shelley, a clerk at Bodley Head publishers whom Wilde was courting and would take to bed that night at the Albemarle Hotel. He encouraged his inner circle of admirers and also one of the cast to wear green carnation buttonholes for the opening and whilst most thought it was a typical enigmatic gesture of Oscar's, others knew it to be a symbol in France of homosexuality. Though the structure of the play was entirely conventional, its wit and satirical edge were unlike anything else being played at the time. At the end, after rapturous cries of 'Author!' from an audience who knew they'd witnessed a special event, Wilde appeared from behind the curtain, took a pull on the cigarette in his mauve-gloved hand (out of nervousness, someone said) and made a memorable short speech:

"Ladies and gentlemen, it's perhaps not very proper to smoke in front of you, but it's not very proper to disturb me when I'm smoking! I have enjoyed this evening immensely. The actors have given us a charming rendering of a delightful play, and your appreciation has been most intelligent. I congratulate you on the great success of your performance, which persuades me that you think almost as highly of the play as I do myself."

The good ended happily, and the bad unhappily. That is what fiction means.

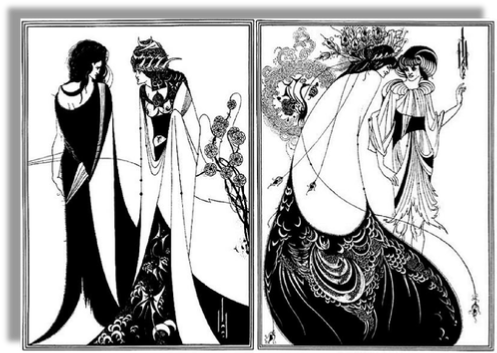

Oscar Wilde was now certainly the most sought-after man in London. He'd once cast lilies at the feet of Sarah Bernhardt and written her a sonnet, but it was now her turn to be his admirer and she agreed eagerly to play the title role in Salome. A macabre piece, written in French, it nevertheless went into production but had to be halted after three weeks' work when it was banned by the Lord Chamberlain because of its use of biblical characters. (Above: Two of Aubrey Beardsley's famous illustrations from the published version of Salome). Wilde threatened to leave the country if the decision was not reversed. Instead he took a rest from his busy work schedule and social life and in July 1892 visited Bad Homburg, Germany with Alfred Douglas.

Refreshed, he came back to work on his new play A Woman of No Importance at a rented farmhouse in Norfolk, accompanied by his family and Douglas. After a week Constance and the children left to holiday in Torquay. Still completely oblivious to her husband's sexual proclivities, Constance had no idea that Oscar had sent £3 to Edward Shelley, inviting him down to the farmhouse for sexual relaxation with himself and Douglas. But Shelley had declined. He was now partnering John Gray - both of them now Oscar cast-offs, usurped by Bosie Douglas. Despite Douglas staying on, and falling ill, Wilde still finished the play and delivered it in October for production to start. (Below: Snapshots of the break in Felbrigg, a village near Cromer, Norfolk, September 1892).

A Woman of No Importance opened on 19th April 1893. Dignitaries at the opening night included Balfour (who became Prime Minister in 1902) and Joseph Chamberlain, with playboy the Prince Of Wales attending the second night. At the end of the first performance Oscar appeared before the curtain only to say "Ladies and Gentlemen, I regret to inform you that Mr. Oscar Wilde is not in the house." The acclaim for this new comedy was the equal of his last. One critic said that Wilde's play 'must be taken on the very highest plane of modern English drama' (William Archer). Others have seen the erotic sub-plot in the play, with Wilde as usual flaunting the duality of his life and beliefs in the audience's face, concealed in code made up of a mass of epigrams, melodrama and Victorian theatrical artifice. Years later Lytton Strachey summed it up over-crudely as follows:

"A wicked Lord staying in a country house, has made up his mind to bugger one of the other guests - a handsome young man of twenty. The handsome young man is delighted; when his mother enters, sees his Lordship and recognises him as having copulated with her twenty years before, the result of which was - the handsome young man. She appeals to Lord Tree not to bugger his own son. He replies that that is an additional reason for doing it (oh! he's a very wicked Lord!)."

That evening Wilde dined at Blanche Roosevelt's house (American opera diva and writer) where the guests had their palms read by society palmist Cheiro through a curtain so he couldn't see his subject. Cheiro told Wilde: "The left hand is the hand of a king, but the right that of a king who will send himself into exile." Wilde asked when and was told, "A few years from now, at or about your fortieth year". Spot on!

One should always be in love. That is the reason one should never marry.

Two of Beardsley’s

controversial illustrations

For Salome

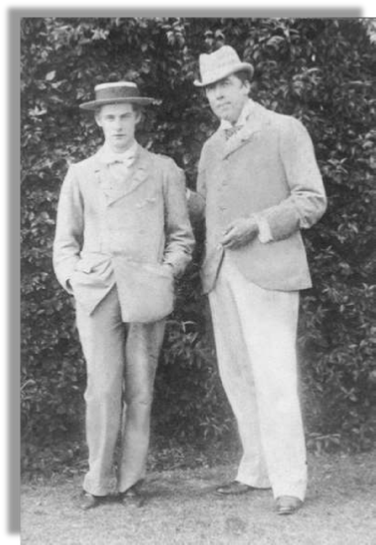

Felbrigg, Cromer summer 1892. L: Oscar, Cyril and Constance. R: Bosie and Oscar.

Although Constance always seemed to carry a wan look, she looks unhappy here. Bosie was supposed to visit for one night but stayed on. Constance left with the boys for Torquay.

Lord Alfred Douglas claimed that his acquaintance with Wilde had been slight since they first met in June 1891 but in spring 1892 Douglas had asked for his help and it was at this time they really fell in love. Douglas had been wildly promiscuous at Oxford and had slept with not just undergraduates but with servants, grooms and assorted other youths. As a result of this he received a blackmail threat that sent him into blind panic and he turned to his brother, Drumlanrig, for help who in turn wrote to Wilde. Bosie also wrote directly to Wilde begging him for help. Wilde got his solicitors to pay £100 in full settlement through an intermediary but nearly all involved were appalled at the details of the behaviour that had given rise to the situation. It was as if Oscar had saved Bosie's life and both were now bound to one another. Douglas became fascinated by Wilde's genius, the enchantment of his conversation and generosity of his spirit, but was not over-enamoured physically. Oscar felt he'd at last met the life-affirming, all-consuming passion he'd always been searching for and he was also strangely, and fatally, beguiled as usual by paradox - he loved Bosie for his vices and his virtues. The two men became inseparable.

Bosie introduced Wilde to the rough trade 'rent boys' who would do anything for a few pounds and a good dinner, and with Bosie's encouragement Wilde stepped up the pace of his casual affairs in the autumn of 1892. Over the next few months Oscar stayed away from home, preferring instead lavish hotels, ostensibly to work on his plays uninterrupted, but really so he could play uninterrupted as well. The proprietors of these hotels became uneasy about the type of acquaintances Wilde was entertaining. They were mainly teenagers, who would return to haunt Wilde as witnesses for the prosecution in his trials: Alfred Taylor, Sidney Mavor, Fred Atkins, Robert Clibborn, Ernest Scarfe, Alfred Wood and others. Most were already accomplished blackmailers. As Oscar said: "It's like feasting with panthers - the danger is half the excitement." Bosie passed Alfred Wood on to Wilde but went on seeing Wood, giving him some cast-off clothes that had one of Wilde's love letters in one of the pockets. Wood sent a copy of one of the letters to Beerbohm Tree, actor manager, then rehearsing A Woman of No Importance, and he tipped Wilde off. Wilde gave Wood and an accomplice £30 for the original. The letter was addressed to Bosie in January 1893 and would be later read aloud at Wilde's trials:

"My Own Boy, Your sonnet is quite lovely, and it is a marvel that those red rose-leaf lips of yours should have been made no less for music of song than for madness of kisses. Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry. I know Hyacinthus, whom Apollo loved so madly, was you in Greek days....."

Other more respectable members of Wilde's troop were becoming dismayed at his recklessness and Bosie's toxic influence. One, Pierre Louys, observed a painful scene at the Savoy where Wilde had rooms with Douglas and there was plainly one double bed and two pillows. Constance arrived unexpectedly to bring her husband's mail, seeing so little of him. He pretended he'd been away so long he'd forgotten the number of his house and Constance smiled through her tears. Louys says Wilde made an aside to him "I've made three marriages in my life, one with a woman and two with men!" (Presumably Douglas and either Robert Ross or John Gray). Wilde himself remarked to Dame Nellie Melba, opera singer, how he'd been telling his sons stories one night about little boys who were naughty and made their mothers cry, and what dreadful things would happen to them if they weren't better. One of them answered "What punishment would there be for naughty papas, who did not come home till the early morning, and made mother cry far more?"

The punishment for that would be severe indeed.

No man is ever rich enough to buy back his past.

Meanwhile, Alfred Douglas's father, the Marquess of Queensberry was on the rampage. He was convinced his eldest son Drumlanrig, private secretary to Lord Rosebery, Foreign Minister (and Prime Minister next year), was having a homosexual affair with Rosebery. His second son Percy, married a clergyman and Queensberry was a staunch atheist, and his youngest Bosie, was being seduced "By that bugger, Wilde". To add to his woes, Queensberry married for the second time in November 1893 and his wife, Ethel Weedon, left him immediately, starting proceedings for annulment on the intriguing grounds of 'malformation of the parts of generation' and 'frigidity and impotence', despite having sired three children! He demanded Wilde stop seeing Bosie and Wilde even weighed in with a letter to Bosie's mother strongly suggesting her youngest be sent to Cairo in the diplomatic service to stop Bosie's life being so "..aimless, unhappy and absurd." Years later there emerged the real motive for Wilde wanting to send Bosie away. Robert Ross had invited Claude Dansey (see Footnote 3), a seventeen year old son of a retired army colonel to his home in London, seduced him and mentioned it to Douglas who rushed there and took the boy back to the Goring-On-Thames house where he slept with both Douglas and Wilde. The boy's father found out and all hell broke loose. Colonel Dansey was persuaded by Wilde's solicitors not to tell the Police because his son could be imprisoned also. Ross's relations found out and he was in disgrace. Lady Wilde, Bosie's mother, was kept in the dark. And Oscar failed again to heed the warning signs.. Douglas refused to go to Cairo, detecting Oscar's attempted coldness but, manipulative as ever, finally agreed as long as he and Oscar were reconciled beforehand.

With Bosie's departure in November 1893 Oscar felt relieved and got on with his work, not least because money was running short - the costs of the three-month stay in Goring had been enormous - and in today's terms Wilde had been spending between £5,000 to £8,000 a week. He completed An Ideal Husband as well as working on A Florentine Tragedy during this very productive period whilst Bosie's antics in Cairo were causing the usual concerns to his diplomatic employers there. They corresponded regularly but Wilde's letters became colder until Bosie realised he'd got to do something. Typically, he wrote to Constance, who rightly resented and despised him, and begged her to intercede on his behalf, which she unaccountably did. He also sent telegrams to Oscar intimating suicide. Oscar capitulated and they met for a glorious reunion in Paris in March 1894.

Education is a wonderful thing, provided you always remember that nothing worth knowing can ever be taught.

In a blaze of glory after the opening of A Woman of No Importance Oscar went for a prolonged stay with Douglas at Oxford University where Bosie was struggling to achieve academic success without doing any work for it. (See photos below of Oscar and Bosie at Oxford. May 1893). He didn't show up for his Greats in June 1893, and left without a degree in order to devote the summer to pleasure. Living almost entirely at Oscar's expense, who was spending his copious royalties as fast he received them, he persuaded Oscar to rent a house at Goring-On-Thames, with eight servants, where they entertained friends as well as having Oscar's family to stay. Oscar began his next play, An Ideal Husband, amid fits of rage and jealous frustration from Bosie who was only too aware of his academic failure and pigmy writing talents compared to Oscar's. So Oscar gave him the project of translating Salome for an English edition but this made things worse as it pointed up Bosie's ignorance even further. Oscar's rejection of his efforts sent Bosie into more fury that he expressed in vituperative letters. Oscar saw his chance to take a different path and tried to break permanently only to relent when Bosie wilted, realising he could lose Oscar. Douglas thrived on quarrels, as he did for the remaining fifty years or so of his life, never coming to realise how much restless energy he wasted this way instead of applying it to achieving something. But vicious arguments drained Wilde considerably, and Douglas must have known this.

Oscar and Bosie at Oxford May 1893, poses from same session

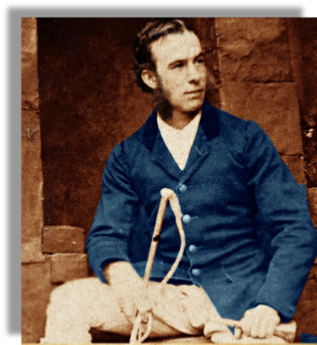

John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry 1844-1900.

L: in his 20s and R: aged 52 in 1896 the year after putting Wilde on his ‘beam ends’ as he put it.

It’s very likely that he died of syphilis as he was only 56 but died of ‘a serious illness of a paralytic nature’. This could also explain his almost demented behaviour and violence of temper.

Children begin by loving their parents. After a time they judge them: rarely if ever do they forgive them.

On 1st April 1894 Wilde and Douglas were back in London lunching at a favourite haunt, the Cafe Royal when Bosie's father came in, enraged by the sight of son reverting to his old habits. But after joining their table he fell under the spell of Oscar's immense charm and seemed to relent. This only lasted until he got home whereupon he wrote a letter to his son expressing his disgust and disappointment with Bosie's feckless existence. Never able to accept the mildest criticism, Bosie sent a telegram to his father the next day saying simply: "What a funny little man you are", which was guaranteed to send the Marquess into apoplexy. The feud got hotter between them and Boise took to carrying a pocket pistol, saying in another vicious letter to his father: "..and if I shoot you or he shoots you, we shall be completely justified, as we shall be acting in self-defence against a violent and dangerous rough".

On 30th June at around four o'clock in the afternoon Queensberry called unannounced at 16 Tite Street with a 'minder' and vented his fury at Wilde, who later said that the Marquess "..had stood uttering every foul word his foul mind could think of, and screaming the loathsome threats he afterwards with such cunning carried out." The undertone of threatened violence obviously shook Wilde. Queensberry prowled London's restaurants in an attempt to repeat the scene in public whilst Douglas continued to taunt him. The dangerous quarrel exhilarated Bosie but Wilde's other friends warned him against coming between the two unstable Douglas's. Letters were exchanged between Wilde's and Queensberry's solicitors intimating proceedings each side might take, with Queensberry also threatening to go to the Police. Wilde and Douglas grossly underestimated Queensberry's cunning.

Choosing to avoid the public scene Queensberry was seeking (Wilde: “It’s intolerable to be dogged by a maniac”) and being strapped for cash as usual, Wilde and his family went to Worthing from August to October where he wanted to concentrate on writing his next play The Importance of Being Earnest on which he'd already received an advance. Luckily, his best play flowed from his pen effortlessly. Despite Oscar discouraging him, Bosie visited three times, noting that relations between Oscar and Constance were strained, even though he knew the chief reason was his presence. The brutal truth, which Bosie knew, was that Oscar was extremely bored with Constance and domesticity, even though he could play the devoted parent with ease if and when he wished. In August Oscar and Bosie picked up two boys on the beach, Stephen and Alphonse Conway. The four of them went fishing and Alphonse was even introduced to Oscar's sons, Cyril and Vivyan who were now nine and seven years old. When the children had gone back to London Oscar brought Alphonse, aged 16, to the house a number of times for dinner and sex games, as well as taking him to a Brighton hotel for more of the same (see Footnote 4).

In this world there are only two tragedies; one is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it.

October 1894 was a bad month for the 'scarlet Marquess' (as Wilde had dubbed him). His marriage was annulled on the 20th but on the 18th his eldest son Drumlanrig, heir to the title, died in a shooting accident in a turnip field, while separated from the main party. Suicide was generally accepted given the shotgun wound was in the mouth (see Footnote 5), and Queensberry attributed his death to the 'secret' love affair he was convinced he was having with the 'Snob Queer' Lord Roseberry. Wilde had had a bad month also. Bosie was bored of Worthing and insisted Wilde treat him at the Hotel Metropole (Ellman has the Grand) in Brighton instead. Bosie caught the 'flu and Oscar nursed and read to him for five days. They then took lodgings in Brighton instead so Wilde could get on with The Importance of Being Earnest but now Oscar went down with 'flu. This didn't fit in at all with Bosie's entertainment plans and he not only didn't bother attending to Oscar, who couldn't even get up for water, but he let fly one night with an outburst that terrified Wilde. He repeated this the following morning and Oscar became convinced Douglas had gone mad and was about to kill him. Douglas scooped up Oscar's money from the side table and swept out, booking himself back into a hotel and on the 16th October, Oscar's fortieth birthday wrote him an astoundingly cruel letter in which he also gloated that he was chalking the bill up to Wilde. That should have been the final parting of the ways. Of course, when Oscar saw the announcement of Drumlanrig's death in the newspaper a few days later he forgave Bosie entirely and as Ellman put it "the old dance began again".

An Ideal Husband opened January 1895. The Prince of Wales and everyone who mattered were in the audience and the play was another hit. Victorian hypocrisy was writ large: London society was only too happy to embrace Wilde's brilliance whilst at the same time gossiping disapprovingly at his shocking behaviour with his 'boy' Bosie. Meanwhile The Importance of Being Earnest, A Trivial Comedy for Serious People was going into rehearsal. It was as if all of Wilde's triumphs, excesses and indiscretions were now all compressed together and spinning faster and faster towards some horrible climax. In January Wilde and Douglas went off to Algiers for three weeks to sample the delights of Arab boys and hashish. He commented there to Andre Gide who was imploring Oscar to be prudent: "Prudent! How could I be that? It would mean going backward. I must go as far as possible. I cannot go any further. Something must happen...something else..." Gide found that Oscar had "..less softness in his look, something raucous in his laughter and something frenzied in his joy." Oscar introduced Gide to young Arab boys who then gave in completely to his latent tendencies. Meanwhile Bosie was seriously trying to 'elope' with a young Arab boy, Ali, who was thirteen!

As the opening night of The Importance of Being Earnest approached - Valentine's Day 1895 - Wilde heard that Queensberry intended to show up, present Wilde with a bouquet of vegetables and address the audience, creating the public scene he was determined to bring about. He'd been in Scotland mourning the loss of Drumlanrig but had heard about Bosie's trip with Wilde to Algiers, and he was incandescent with rage. The theatre had sent him a refund for his ticket and the Police were alerted, the theatre entrances guarded, and he was prevented from making his scene. Resplendent with green carnation Wilde savoured yet another success: he now had two hit plays in the West End simultaneously. Dashed off in a hurry to meet debts, Earnest marked the apogee of Wilde's career as a dramatist and again dealt with the problems of a man leading a double life in high society, as Wilde had done now for ten years. The play is littered with references to Oscar's 'Uranian' life and friends. Among that circle the word 'earnest' signified gay and was a corruption of the French Uraniste.

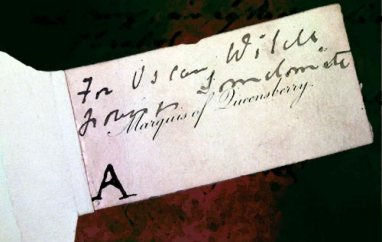

Bosie, having heard about his father's attempted theatre scene now rushed back from Algiers to lead the charge against his father. He went on incessantly to Oscar about getting his father in the dock, as usual not thinking for one moment about anything else but his own desires. On 12th February 1895 Queensberry, in an explosion of frustration, marched into Wilde's club the Albemarle and, finding him not there, hurriedly scribbled a comment onto one of his calling cards and left it with the porter, Sydney Wright. Wright saw the comment and put the card in an envelope for Wilde to pick up when he next came in. This is the infamous card, now in the British National Archives, the large ‘A’ is its trial exhibit number:

Since the card came to light in the National Archives there's been dispute as to what the card actually said. When Sydney Wright gave evidence in the first trial, Wilde's criminal action for libel against Queensberry, he said he read it as 'ponce and somdomite' and thought it best to pop it in an envelope to await Wilde's next visit. At this point Queensberry interjected to say he'd written 'posing as sodomite'. There's an important distinction. Queensberry had probably been advised that 'posing as sodomite' was easier to defend than 'posing sodomite'.

One of the ideas most frequently explored in his work is the sudden exposure of a guilty secret and the individual's subsequent disgrace. Wilde often said that life imitated art and in his own case this was to prove only too true. Encouraged by Douglas, Wilde sued the Marquess for criminal libel. This was not a sensible course of action, since the accusation was obviously true. Wilde was forced to abandon the suit. This was not the end of the affair, however. Having been publicly shown - in a court of law - to be a sodomite, it was only a matter of time before criminal proceedings began. Wilde was arrested and brought to stand trial. His friends had pleaded with him to flee the country at the end of the original lawsuit, but Wilde had been convinced he would never be prosecuted.

Experience is the name everyone gives to their mistakes.

The criminal trial failed to reach a verdict. Written accounts attest that Wilde performed spectacularly under cross-examination, but the jury failed to reach a unanimous decision. A retrial was ordered and this time Wilde was found guilty of gross indecency. Mr Justice Wills was the judge on that occasion. For a detailed account of the trials go to my OW page ‘The Trials’.

The truth is rarely pure and never simple.

Wilde spent two years in prison. Whilst incarcerated his mother died, in February in 1896. She had requested to see her son for the last time and this was refused by the authorities.

A prison chaplain wrote:

When he first came down here from Pentonville he was in an excited flurried condition, and seemed as if he wished to face his punishment without flinching. But all this has passed away. As soon as the excitement aroused by the trial subsided and he had to encounter the daily routine of prison life his fortitude began to give way and rapidly collapsed altogether. He is now quite crushed and broken. This is unfortunate, as a prisoner who breaks down in one direction generally breaks down in several, and I fear from what I hear and see that perverse sexual practices [masturbation] are again getting the mastery over him. This is a common occurrence among prisoners of his class and is of course favoured by constant cellular isolation. The odour of his cell is now so bad that the officer in charge of him has to use carbolic acid in it every day.... I need hardly tell you that he is a man of decidedly morbid disposition.... In fact some of our most experienced officers openly say that they don't think he will be able to go through the two years.

Most of this was served at Reading Gaol, where he was put to hard labour, and from there he wrote a long, angry letter to Lord Alfred Douglas blaming the man for his role in Oscar's fall from grace. This was later published, in an edited form, as ‘De Profundis’.

I never saw a man who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

Which prisoners call the sky

Wilde was released from prison in 1897. Bankrupt, disgraced and unwanted by society, he returned to France where he hoped to re-establish himself as a writer. Sadly, his only remaining work was to be The Ballad of Reading Gaol. This was published in 1898 under the pseudonym C.3.3 - his prison identification number. It is widely regarded as his best poem.

A man cannot be too careful in his choice of enemies.

And what of Bosie? His punishment was to outlive all involved in the Wilde tragedy, dying aged 74 of a heart attack on 20th March 1945 in Lancing, West Sussex at the farm home of Edward and Sheila Coleman who looked after him for his last few months. They became his literary executors. For some years Bosie had lived in reduced circumstances, selling some of his possessions to raise funds and relying on others.

He’d spent 40 years coming to terms with his relationship with Wilde during which time he repudiated his homosexuality and became a frequent visitor to the courts, firing off law suits at the drop of a hat as soon as he spotted what he thought were defamatory references to him in connection with Wilde. He wrote four books about himself and Wilde. Over the years these became less vituperative culminating in Oscar Wilde: A Summing Up (1940) where he seems to reach some kind of reconciliation with his memories and feelings after spending a lifetime wishing they were different: “Sometimes a sin is also a crime (for example, a murder or theft) but this is not the case with homosexuality, any more than with adultery”.

In 1902 Bosie married Olive Custance, a bi-sexual poet. Her father, a wealthy Colonel in the army, deeply disapproved and they eloped in order to marry. Although it seems Bosie very much loved Olive his motives were partly financial as he’d taken a trip to the USA a year before specifically to find himself a rich heiress. It was all the rage at the time - wealthy American girls marrying into a titled family and the latter’s finances becoming bolstered into the bargain. Bosie had been seeing Olive before the trip and when he returned without his ideal heiress he pursued Olive more earnestly. The marriage produced one child, Raymond, who was born at the end of 1902. Sadly, he showed his membership of the ‘mad bad line’ of Douglas’s by becoming mentally unstable and spent virtually all his life in institutions, dying in 1965. Bosie and Olive separated in 1913 but lived together for a while again in the 1920s. Olive in February 1944, a year before Bosie.

Simon Callow in his book Oscar Wilde and his Circle comments on Bosie’s features shown in the two photos below right:- “From golden youth to crazed litigant…He too was punished, condemned to the living hell of being trapped inside his own personality”.

No good deed goes unpunished

Footnotes

1. Oscar had two two children. Cyril (b. 1885) died in The First World War as mentioned above. Vyvyan Holland (b. 1886) died in 1967 aged 80. In 1945 he had a son, Merlin Vyvyan Holland, by his second wife. Merlin has one son, Lucien (b. 1979), so is Oscar Wilde's only great-grandchild. Lucian studied classics at Magdalen College where he was given rooms which Oscar Wilde had once occupied. His grandfather, Vyvyan was refused a place at Oxford in 1905 because of that connection. He took up law at Cambridge instead.

I find it very odd that they all chose to keep the name Holland. Merlin hinted once that he might change it back to Wilde but has never done so.

2. All references to ‘Ellman’ are to Richard Ellman’s major 1987 Pulitzer Prize winning biography of Wilde. Ellman’s book contained a few errors and a lot more research has been done since then and more information brought to light. A long overdue new biography was published in 2018: ‘Oscar’ by Matthew Sturgis, a 656-page, magnificent, superbly-written work which at present is the definitive word on Wilde’s life.

3. Ellmann's biography of Wilde has 'Philip Danney', a confusion with Philip Wortham, a fourteen-year-old seduced by Ross. Dansey had stayed with the Worthams. Claude, later Sir Claude, Dansey, went on to become a controversial character in WW2. In 1895, two years after the scandal with Wilde, Ross and Douglas, and the year of Wilde’s downfall, he joined the South African Police aged 19, then the British Army three years later. During WW1 he was recruited by MI5 and helped set up the first American military intelligence service in 1917. In 1939 he became deputy to Stewart Menzies, chief of MI6 (SIS). He controlled thousands of spies in Europe and was head of the shadowy “Z” operation, which ran without the knowledge of the SIS. Some say Dansey was responsible for the catastrophic betrayal of the SOE’s ‘Prosper’ network in France during WW2, one motive (weak surely?) was that MI6 bitterly resented the activities of SOE. The book “All The King’s Men” by Robert Marshall deals with this intriguing, unresolved controversy. Dansey retired in 1945, dying two years later aged 70. His youthful gay leanings are thought to have continued throughout his life. (Numerous homosexuals rose to high office in the security services in the first half of the twentieth century seemingly without hindrance, some infamous ones betraying their country to the Soviets for decades: Burgess, Blunt, and bisexuals Philby and McLean). Dansey married twice - for appearances presumably - but had no children.

4. If anyone's curious, Wilde's preferred sexual activity was masturbating his partners and fellating them. There's no evidence he took part in anal sex, passive or otherwise. Bosie, however was a prolific practitioner of active anal sex but swears he was never a passive recipient, which would have been seen as degrading to someone of his class.

5. Bizarrely, Drumlanrig's death was identical to that of his grandfather, Archibald Douglas, 7th Marquess of Queensberry, except his wound was in the chest.

More than a century after his death, Wilde is remembered for his personal life - his exuberant personality, consummate wit and infamous imprisonment for homosexuality - and his literary accomplishments. His witty, imaginative and undeniably beautiful works, in particular his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray and his play The Importance of Being Earnest, are considered among the great literary masterpieces of the late Victorian period. His enduring relevance and popularity as largely due the mirror-like nature of his writings, particularly his epigrams, whereby the reader receives a reflection of their own nature in return.

Throughout his entire life, Wilde remained deeply committed to the principles of aestheticism, principles that he expounded through his lectures and demonstrated through his works as well as anyone of his era. "All art is at once surface and symbol," Wilde wrote in the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray. "Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril. Those who read the symbol do so at their peril. It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors. Diversity of opinion about a work of art shows that the work is new, complex and vital."

Biography lends to death a new terror

Although Douglas had been the cause of his misfortunes, he and Wilde were reunited in August 1897 at Rouen after emotional communications. This meeting was disapproved of by the friends and families of both men. Constance Wilde was already refusing to meet Wilde or allow him to see their sons, though she kept him supplied with money. During the latter part of 1897, Wilde and Douglas lived together near Naples for a few months until they were separated by their respective families under the threat of a cutting-off of funds. They had also realised, particularly Bosie, that things could never be the same and the flame had died. They still saw each other from time to time in Paris and enjoyed the usual lavish dining. Bosie also gave small cheques to Oscar from time to time, although Oscar continually bleated about his penury to all who would listen. But the truth was he was utterly incapable of moderating his lifestyle to match his income from his allowances and gifts.

In April 1898 his wife Constance died following unsuccessful surgery for a spinal condition caused by a fall at Tite Street some years earlier. She was only 39. Oscar was grief stricken when he heard the news. This also cut off any final chance of communicating with his sons, Cyril now almost 13 and Vyvyan 11. Their guardians took legal steps to ensure no communication was possible, not even by letter.

Wilde's final address was at the dingy Hôtel d'Alsace (now known as L'Hôtel), in Paris; "This poverty really breaks one's heart: it is so stale, so utterly depressing, so hopeless. Pray do what you can" he wrote to his publisher. He corrected and published An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest, the proofs of which Ellmann argues show a man "very much in command of himself and of the play" but he refused to write anything else. "I can write, but have lost the joy of writing".

He spent much time wandering the Boulevards alone, and spent what little money he had on alcohol. A series of embarrassing encounters with English visitors, or Frenchmen he had known in better days, further damaged his spirit. Soon Wilde was sufficiently confined to his hotel to remark, on one of his final trips outside, "My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has got to go."

Wilde never properly recovered from the ill treatment he had received as a convict and a fall he had in jail. Wilde began to suffer from increasingly severe headaches. He was diagnosed as suffering from cerebral meningitis. On 12 October 1900 he sent a telegram to Ross: "Terribly weak. Please come." His moods fluctuated; Max Beerbohm relates how their mutual friend Reginald 'Reggie' Turner had found Wilde very depressed after a nightmare. "I dreamt that I had died, and was supping with the dead!" "I am sure", Turner replied, "that you must have been the life and soul of the party."

Oscar endured some surgery on his ear but was soon confined to bed and became delirious. Ross arranged for a priest to come and receive him into the Church of Rome. Turner was one of the very few of the old circle who remained with Wilde right to the end, and was at his bedside when he died on 30 November 1900.

Bosie arrived the day before the funeral and everyone acknowledged he should be chief mourner, although there was an altercation between him and Ross at the graveside. Bosie paid for the ‘sixth class’ burial in a leased plot just outside Paris, despite the fact he’d been busy squandering his inheritance from the death of his father in January, some £15,000 or £1.5m in today’s terms. He’d bought stables at Chantilly and spent his time racing, gambling and no doubt cavorting with youths.

Nine years later with Wilde’s bankruptcy paid off thanks to Ross’s stewardship of the estate, Oscar’s remains were moved to his present resting place in Père Lachaise cemetery, Paris, beneath a striking monument by Jacob Epstein. Robert Ross’s own ashes were placed there at his request (he died in 1918) in 1950.

I have put my genius into my life; all I've put into my works is my talent.

Oscar on his death bed after he’d been laid out.

The photo was taken by Maurice Gilbert, one of Oscar’s numerous Paris paramours who was also shared with Ross and Bosie Douglas.

Bosie 1903 aged 33

1914 aged 44

Early 1940s - now in his 70s

Click on image to enlarge

Books About Oscar

Searching on Amazon.co.uk for books on Oscar Wilde brings up almost 11,000 entries. To help you here is my list of the essential reading to get you off on the right foot. Click on their titles to go to Amazon.co.uk to see more about them and/or buy them. There’s also a link below where you can search for a particular title on Amazon.

Oscar A Life - Matthew Sturgis 2018

A superbly written and punctiliously researched book taking full advantage of all the new material available since Ellman. Essential reading for budding Wildeans!

Oscar Wilde - Richard Ellman 1987

A ‘magisterial work as they say. Ellman died just as it was published, otherwise it would have been updated for some errors and new research (the photograph of Oscar dressed as Solome isn’t Oscar and I also found a small error, see 3. in box left). Until a long overdue new attempt - see above - this was the go to biography.

The Wilde Album - Merlin Holland 1997

Merlin Holland is Vyvyan Holland’s son, and.Oscar’s grandson. This is a nicely designed book with lots of photos of Wilde and his friends.

Bosie: A Biography of Lord Alfred Douglas - Douglas Murray 2000

Written at Oxford when Murray was only 19 (it was originally his thesis), the Daily Telegraph said of it at the time: 'A precocious feat by almost any standards...An excellent piece of work, intelligent and well-rounded'. It’s a bit of an apology for Bosie and also proposes that his poetry was not second rate, so it’s a brave attempt at the impossible. Nevertheless, a new biogaphy of Bosie was well overdue and it’s a fascinating one.

Constance: The Tragic and Scandalous Life of Mrs Oscar WIlde - Franny Moyle 2013

I think it wrong to have the word ‘scandalous’ in the title; Constance’s life wasn’t. The author tells Constance's story with a fresh eye and remarkable new material, drawing on numerous unpublished letters from the Holland family. Although there have been three previous books about Constance this is the only one that paints a proper, full picture of her and brings her to life as someone with her own interests and pursuits. A must read.

The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde - Neil McKenna 2004

This book relates what couldn’t be told in detail in the immediate decades following Wilde’s downfall - the incredible extent if his, and Bosie’s, unbridled indulgence in young men and boys, all with a breathtaking disregard for possible consequences.

Try and find Bosie’s four books if only to read how incredibly self-serving he was. They never stayed in print for long and unfortunately are very rare now.

Oscar’s tomb at Père Lachaise. L: The endless desecration. In 2011 the authorities renovated the monument, removing all the lipstick and graffiti and adding a protective glass screen. A year later (photo right), barriers had to be erected as idiots damaged an adjacent grave in attempting to access Oscar’s. As the man himself might have said: “Alas, the world is full of selfish, ignorant twats”.

| The 1960s |

| The 1970s |

| The 1980s |

| The 1990s |

| The 2000s |

| The 2010s |

| The Cast Part 1 |

| The Cast Part 2 |

| Videos 1 |

| Videos 2 |

| Billy The Kid |

| Oscar Wilde |

| The Trials |

| De Profundis |